Quite an active weather day along the front range yesterday; part of a string of active weather days for many areas across Colorado. From heavy snow in the mountains to strong winds along the front range, we’ve seen a bit of everything this past week!

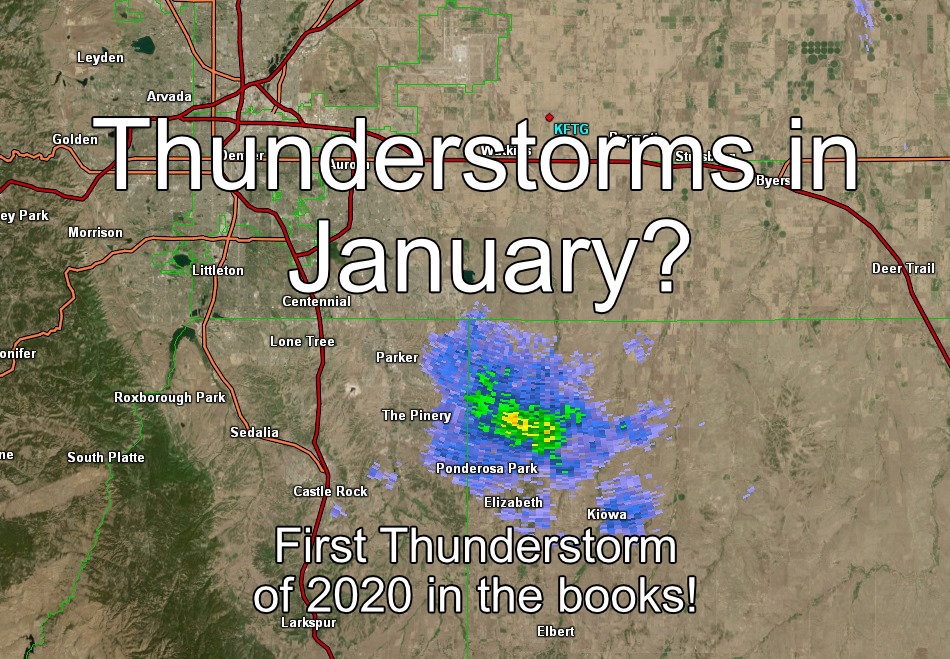

An interesting phenomena happened yesterday as we recorded our first thunderstorm of 2020… in January!

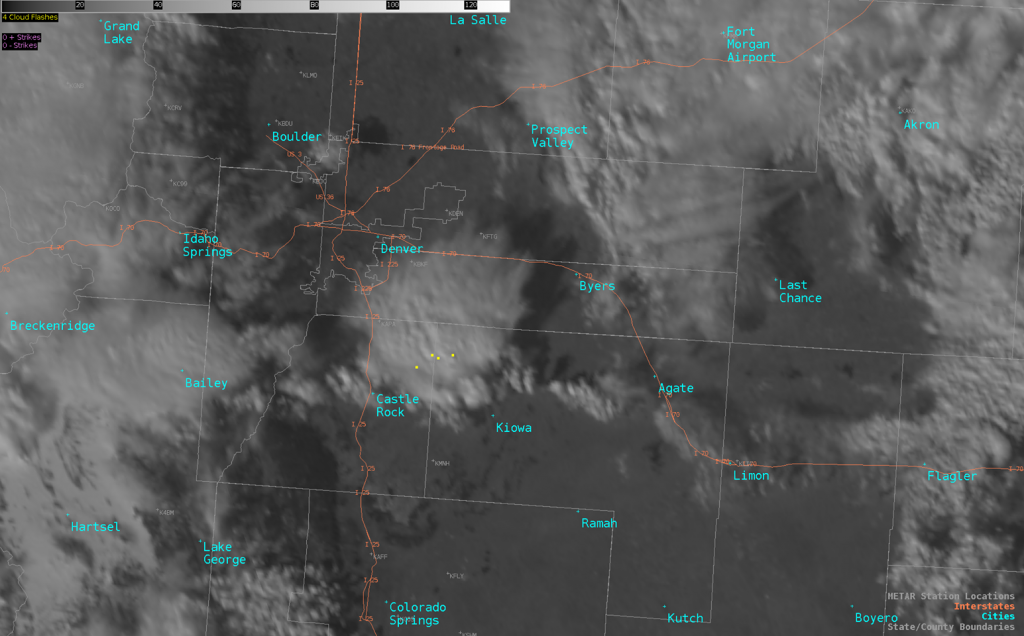

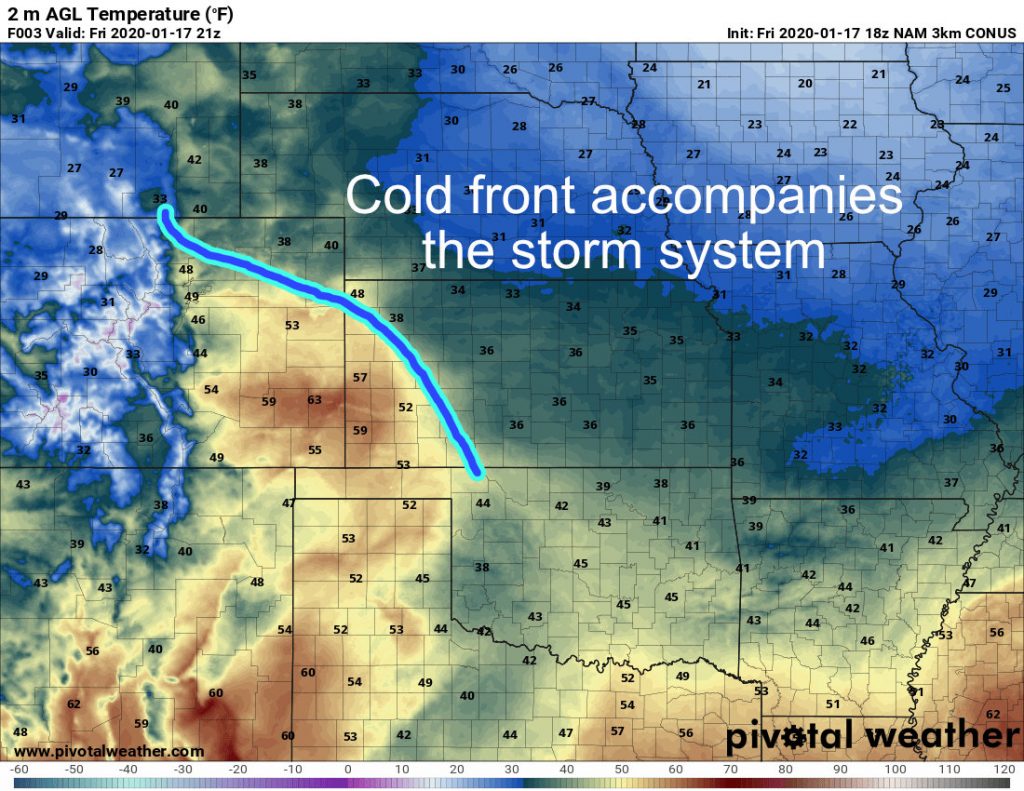

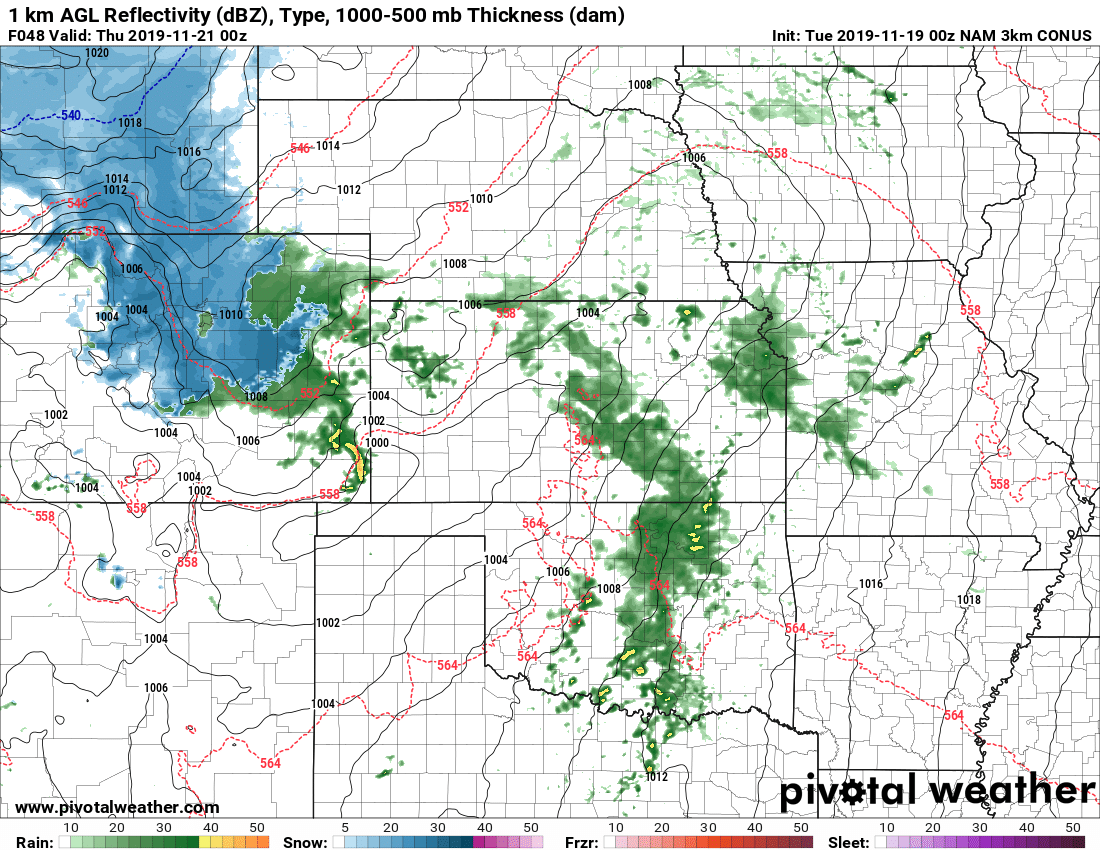

A storm began to from over Eastern Douglas County and moved into Northwestern Elbert County. The yellow dots in the image above represent cloud to ground lightning strikes. Many of our viewers in Parker, the Pinery and areas of Northwestern Elbert County reported hearing thunder as this storm passed through. So mark it in the books, we’ve officially seen our first thunderstorm of the year!

How in the Heck Do Thunderstorms Form in January?

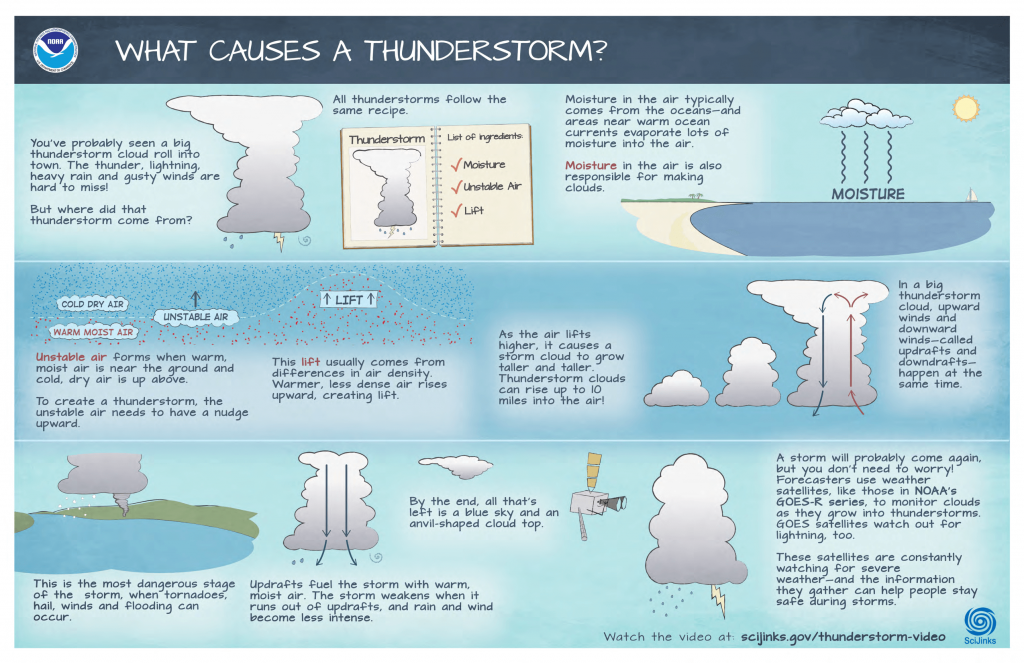

If you’ve followed my page long enough you know I’ve often talked about the ingredients needed to form a thunderstorm:

- Moisture

- Unstable Air

- Lift (a lifting mechanism)

If you have those three in the proper quantities, a thunderstorm can form any time of the year!

A big misconception for a lot of folks is that the mentioned parameters above only apply during thunderstorm season (spring – fall) but really it can happen any time as long as these ingredients all match up.

A Look at Yesterday

So let’s see if all of these ingredients were in place yesterday!

*I’ll try not to get too technical on this but will have to use some weather tools, but I’ll do my best to describe what’s going on without being too** nerdy!

**I make no promises about getting too nerdy!

Moisture?

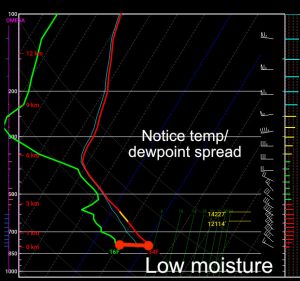

A Skew-T Diagram is a weather tool that tells us what’s going on in different parts of the atmosphere at any one time

Earlier in the day we noticed a high temperature / dewpoint spread, this means that moisture was lacking at the surface so not great conditions for any thunderstorm activity early in the day. The above skew-t was a forecast from Nam3K for around Northwestern Elbert County.

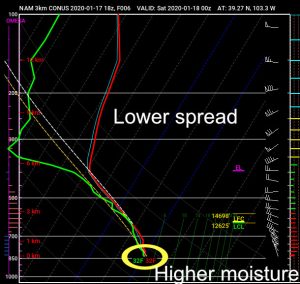

By the afternoon though, things had changed.

As the surface low set up over Eastern Colorado and began to move Northeast we see an influx of moisture at the surface

The influx of moisture seemed to accompany a surface low setting up over Eastern Colorado. This is part of the storm system that would transition out into Eastern Colorado and across the plains and become the major storm system they are experiencing now.

Instability?

If you’re relatively well trained on Skew-T diagrams you can eyeball them usually to see if there is instability or not. Additional plotting and a bit of math is involved to tell how much instability, I’ll leave that part out for now for brevity sake.

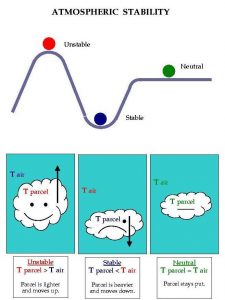

First let’s talk just a bit about what atmospheric instability is.

A parcel of air will rise in an unstable environment, it will sink in a stable environment and will due neither in a neutral environment

The best way to envision instability is take a parcel of air and lift it (in this case we will say by warming it but there are other ways.) As this parcel of air becomes warmer it becomes less dense than the cooler air around it and due to buoyancy it will begin to rise. How dramatic this effect is presented is a measure of how unstable the air is. The more unstable the air, the more violently our parcel of air will lift into the atmosphere. A similar effect is seen when you fill a ballon with helium, the balloon will begin to rise as helium is less dense than oxygen.

Instability is measured by something called CAPE or Convective Available Potential Energy. As a measure of potential energy is it measured in Joules per Kilogram or J/KG

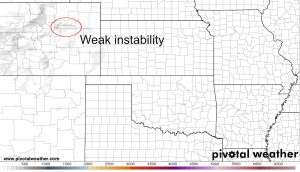

Yesterday as the trough moved Eastward across the plains we see weak areas of lift begin to develop. In a lot of cases a paltry 500 j/kg established right over the Palmer Divide — to simplify that it is instability but weak instability. In Colorado through, we don’t need a ton of instability to form storms. Interesting enough, I imagine that there were pockets of stronger instability for reasons I’ll explain in another article.

Lift?

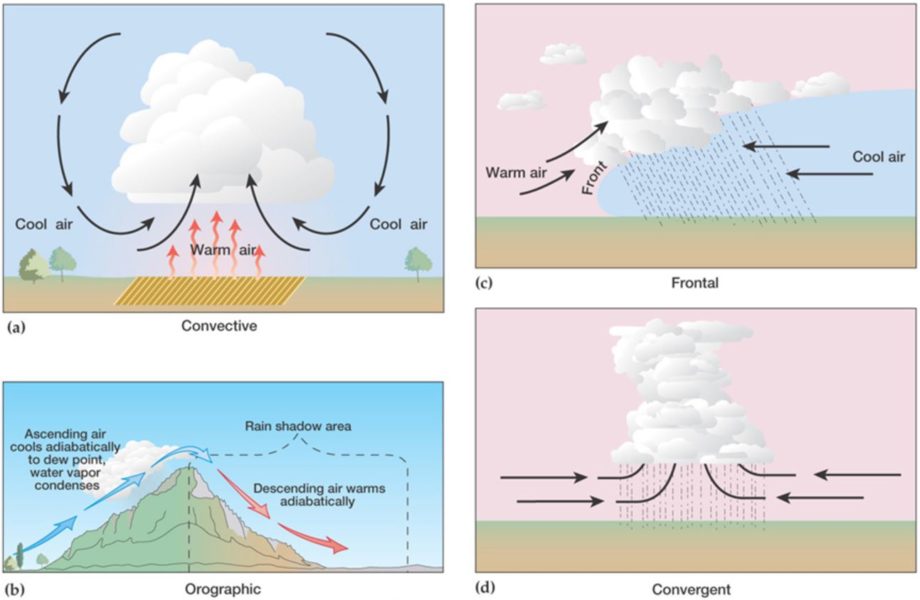

Ok so if we have the first two ingredients, we know moisture is available and we have an unstable atmosphere. This means all we need to do is kick off the process of lifting our parcel of air. There’s a few ways we can do this:

- Convective

- This is caused by air warming due to sunlight, as the sun warms the surface the energy is radiated to the air and in turn that air begins to warm

- Frontal

- A cold front acts like a wedge and cuts through warmer air, this forces the warmer air ahead of the front to begin to rise. The colder air does this because it is more dense.

- Orographic

- This is a big deal in our neck of the woods. Orographic lift is the technical term for what we often call “upslope.” As air rises it cools and condenses and eventually falls down the other side of the hill or mountain and begins to warm and compress. We see this a lot around here!

- Convergent

- We see this a ton in spring along the Palmer Divide and is generally responsible for our thunderstorms, severe storms and tornadoes. The moving one direction crashes into the air moving from another direction and is forced to lift.

In terms of what we saw yesterday, it’s tough to find historical data to present this in a good way (I should have been better about taking snapshots in real-time but I usually can’t do that at my job) I imagine it may have been a mix of factors that caused the air to lift.

A mass of cooler air moved in during the afternoon, could have been a front but wasn’t super strong when all things were considered. Still, it was a wedge of cold air moving into a warmer environment so I’d expect the warmer air at the surface to be driven upwards.

Did We Have Everything?

Moisture?: CHECK

Instability?: CHECK

Lift?: CHECK

Despite the fact it is January, we had all the ingredients in place. Is it any surprise then that we saw a thunderstorm?

Summary

Just another Colorado weather day. If you’ve lived here long enough you’ve learned that we can see wildfires in January, thunderstorms in February, snow in June and tornadoes in October. The best part about Colorado is that you get to see nearly every type of weather over the course of a year and a lot of our weather phenomena can happen almost any time of the year!