How We Get Freezing Fog and Freezing Rain

Freezing Fog, Freezing Rain, Freezing Drizzle in Colorado

What The Heck is Freezing Rain and How Does It Happen?

Freezing rain is supercooled water that exists in a liquid state, even though its temperature is below freezing. When that supercooled water comes in contact with a surface, it instantly freezes and turns to ice.

Most areas near the mountains along the front range do not experience freezing rain often. The simple explanation is that our atmospheric conditions are not often favorable to this type of freezing precipitation. We are far more likely to see snow, sleet, or just plain rain.

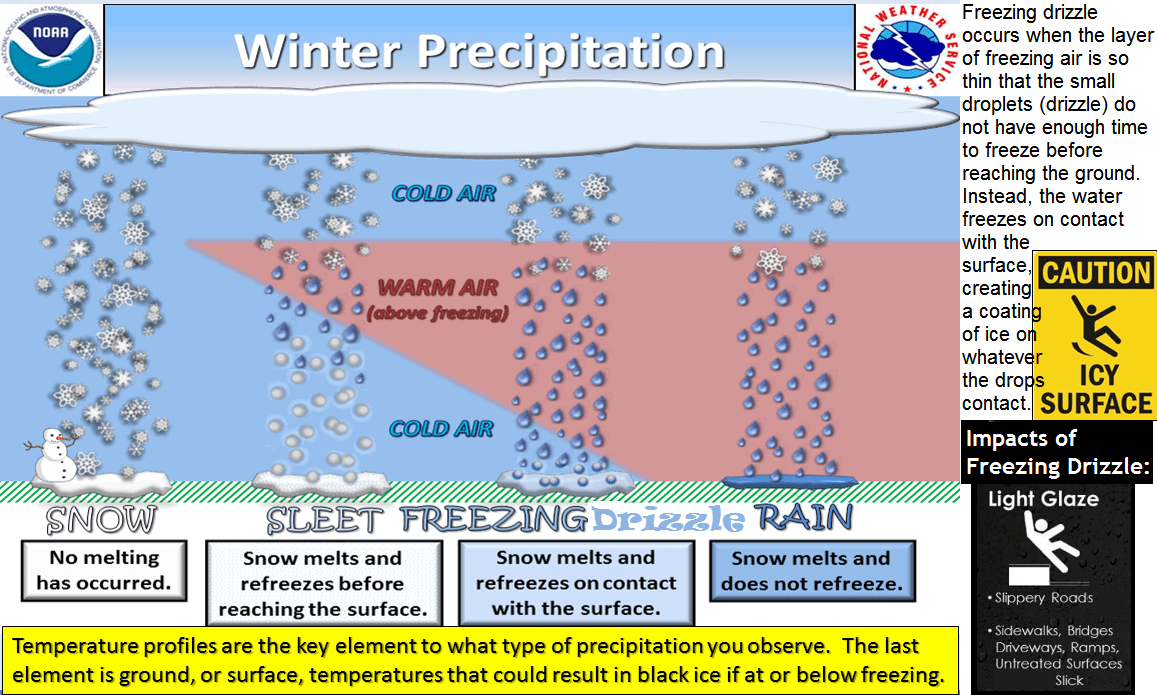

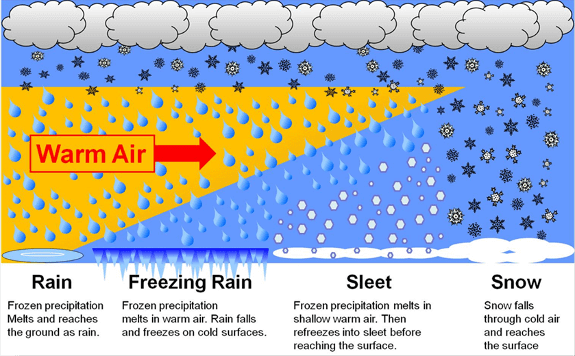

The image above shows what types of precipitation you are likely to get depending on what levels of warmth or cold are present at different heights of the atmosphere. The type of precipitation we get depends entirely on the atmosphere and how the temperature changes with altitude and how much moisture we have at different parts of the atmosphere.

It’s an intricate balance, too much warm air and you’ll see rain. Too much cold air and you’ll see snow. If you don’t have enough moisture in your snow growth zone, you may see other types of mixed precipitation, if you’re saturated in that snow growth zone, what happens below it becomes much more important.

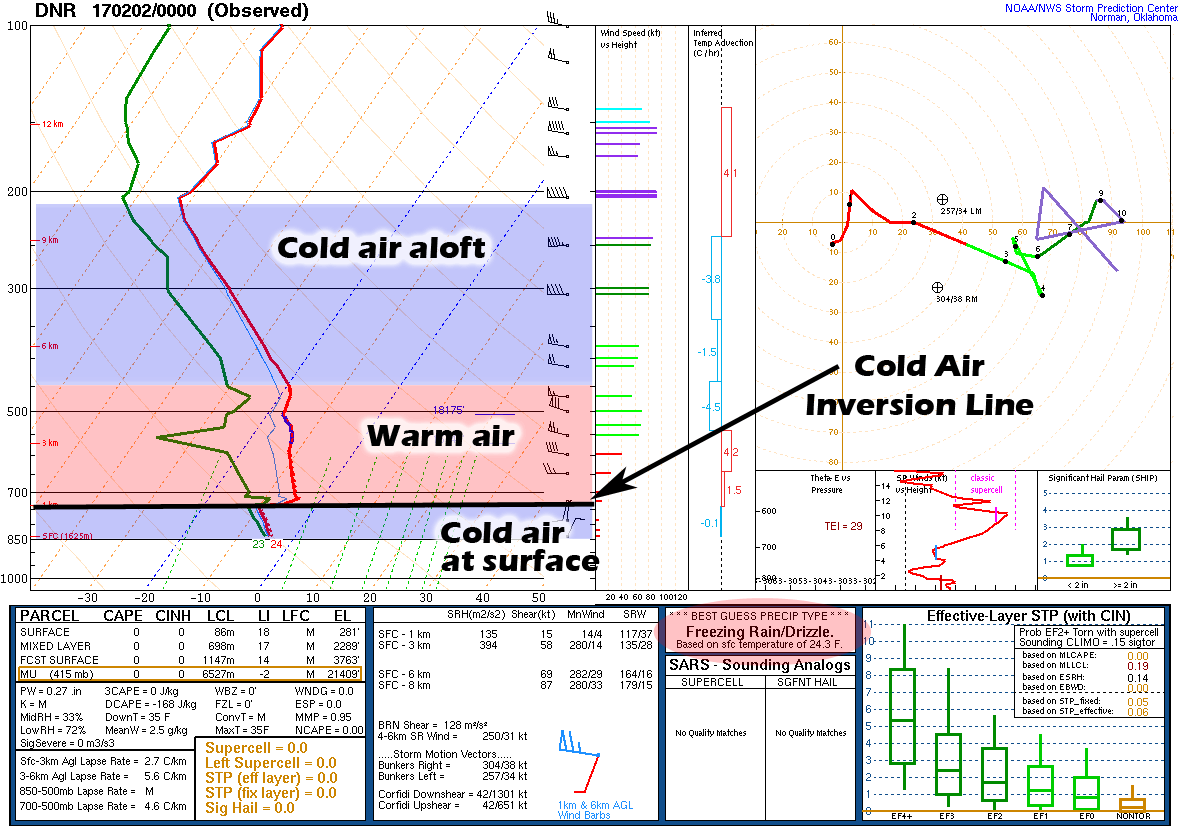

How do meteorologists know the atmosphere’s conditions at different heights, anyway? That’s where our good friend, the Skew-T diagram, comes in. This chart was created twice daily when the National Weather Service released a weather balloon with scientific equipment into the air. Let’s take a look at this sounding from Denver.

Notice how the Skew-T (with some of my notations for temperature) lines up pretty well with the “Freezing Rain” atmospheric profile above. Another key ingredient here is the red (temperature) and green (dewpoint) lines are very close together at the surface (near the bottom of the Skew-T) This means the atmosphere is nearly saturated (lots of humidity in the air) and is an important step because if the atmosphere were cold and dry, precipitation falling would have a better chance to re-freeze into ice pellets or snow.

What About Freezing Fog?

Freezing fog has the same principle as freezing rain but the process for it happens near the surface rather than falling through the atmosphere. At the end of the day, what fog basically consists of is water droplets, in essence its a cloud.

Freezing fog is when those water droplets are allowed to exist in a liquid, super-cooled state… much as the freezing rain discussion above. When the air is saturated enough and exists at a low enough temperature you can see these conditions. Freezing fog is dangerous just like freezing rain because it will exist in a liquid state only until it comes in contact with a surface…

Once it hits that surface it will begin to freeze and form ice. This is why it can make travel conditions treacherous, once the roads cool enough they can very quickly flash freeze and begin to accumulate ice. Unlike snow, this ice can be invisible and catch people unaware, often leading to bad crashes.

Why Don’t We See This Stuff Very Often?

As I said above, it takes very specific conditions for us to see freezing precipitation along the front range. It’s not enough just to have the cold air aloft, warm air in the middle and cold air at the surface. These layers need to be certain heights and any variation can dramatically change the precipitation we see.

Additionally, we need the lower cold layer of air to be saturated with the proper warm and cold air layers in place. All of these things need to happen perfectly and often we are missing one or two of these closer to the front range, most of all because the air at our surface is usually much drier than areas on the Eastern plains

Want to Know More? Check Out These Related Articles!

About the Author

Meteorologist John Braddock

Position